The Stomach is the part of the alimentary canal between the esophagus and the duodenum. It is the widest and most distensible part.

Synonyms: Gaster (in Greek); venter (in Latin).

Stomach

Functions

The key functions of stomach are:

- Creates a reservoir of food.

- Blends food with gastric secretions to create a semifluid substance referred to as chyme.

- Controls the speed of delivery of chyme into the small intestine to enable proper digestion and absorption in the small intestine.

- Hydrochloric acid secreted by the gastric glands ruins bacteria existing in the food and beverage.

- Citadel’s intrinsic factor within the gastric juice helps in the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

Location

The stomach inhabits the left hypochondriac, umbilical, and epigastric regions. It is located in the upper left part of the abdomen. It flows from the left hypochondriac region into the epigastric region obliquely.

Majority of the stomach is located under cover of the left costal margin and lower ribs.

Shape

The stomach is largely “J” shaped. Its long axis enters downward, forward, and to the right and eventually backward and somewhat upward. It tapers from the fundus on the left of the median plane to the narrow pylorus somewhat to the right of the median plane.

Points to be noted

Both the shape and position of the stomach differ considerably according to the construct of an individual. It’s:

- High and transverse (steer horn type) in short fat individuals.

- Low and elongated in tall and feeble individuals.

Even in the exact same individual the shape of the stomach is dependent upon the:

- Volume of fluid or food it includes.

- Position of body (erect or supine position).

- Stage of respiration.

The shape of the stomach is studied by radiographic evaluation using barium meal. Usually, 4 types of shape of the stomach are viewed in barium meal X-ray.

Size and Capacity

Length: 10 inches.

Capacity: The capacity of the stomach is changeable as the stomach is extremely distensible:

- At birth the capacity is only 30 ml (1 oz).

- At puberty the capacity is 1000 ml (1 L).

- In adults the capacity is 1500 to 2000 ml.

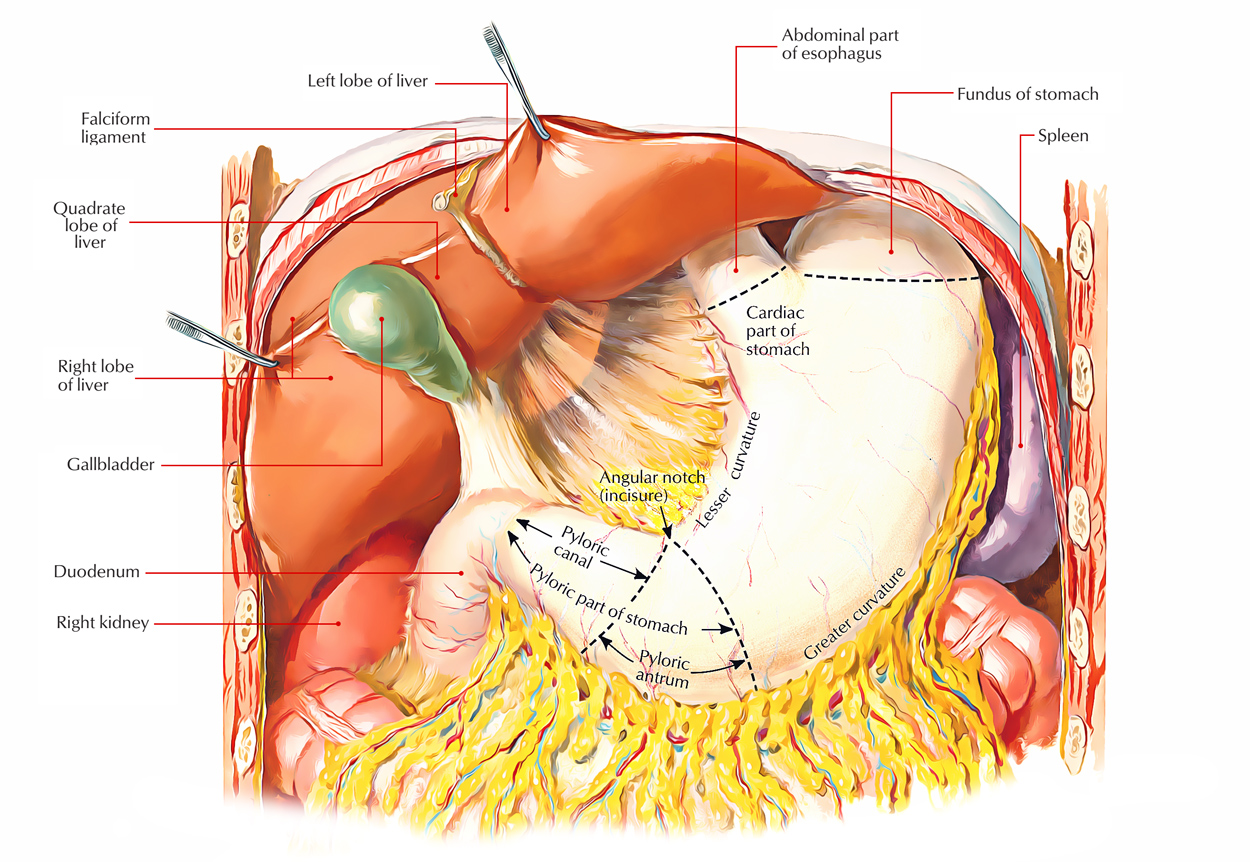

External Features

The stomach presents the following external features:

- 2 ends: Cardiac and pyloric.

- 2 curvatures: Lesser and greater.

- 2 surfaces: Anterior (anterosuperior) and posterior (posteroinferior).

Ends

- Cardiac End (Upper End): It joins the lower end of the esophagus and presents an orifice named cardiac orifice.

- Pyloric End (Lower End): It joins the proximal end of the duodenum and presents an orifice referred to as pyloric orifice.

The stomach is comparatively fixed at upper and lower ends but mobile in between.

The cardiac end of the stomach is less mobile and not as likely to change in position on the other hand the pyloric end of the stomach is more mobile and more inclined to change in position.

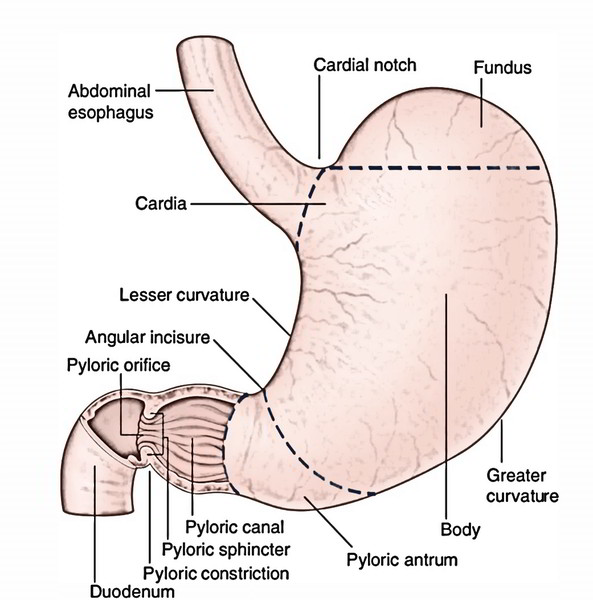

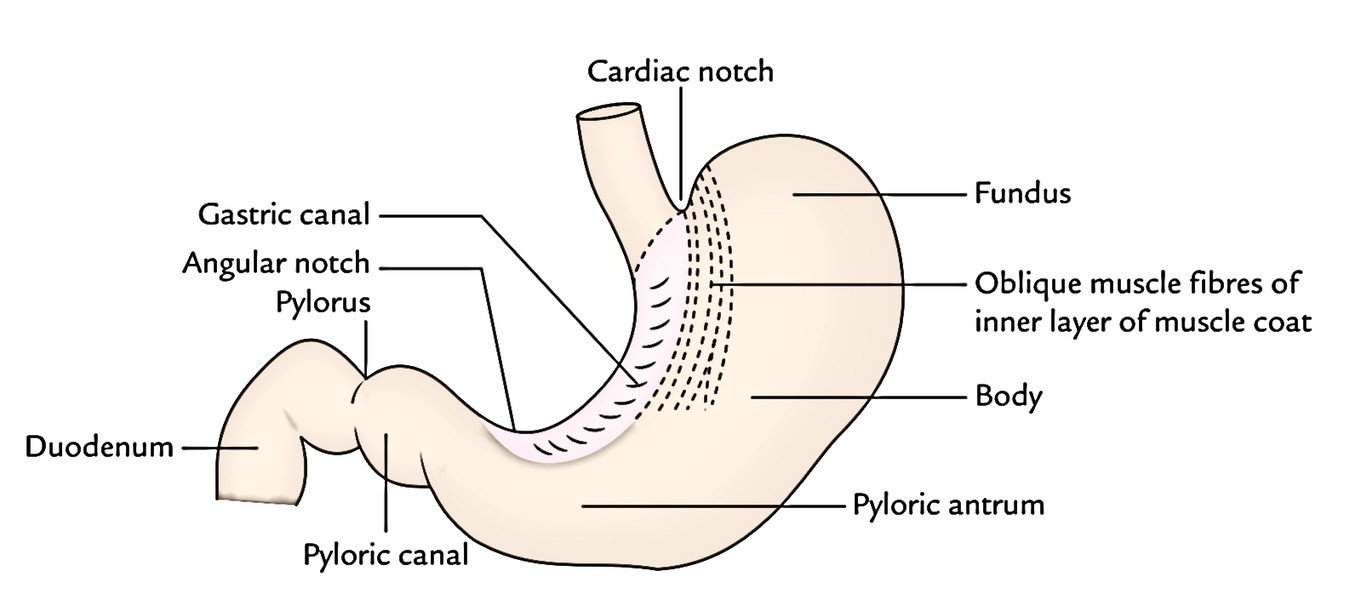

Curvatures

- The stomach presents 2 curvatures- lesser and greater.

Lesser Curvature

- It’s concave and creates the shorter right border of thestomach. The most dependent part of the curvature- theangular notch/incisura angularis, signifies the junction of the body and pyloric part. The smaller curvature gives connection to the lesser omentum.

Greater Curvature

It’s convex and creates the longer left border of the stomach. At its upper end this curvature presents a cardiac notch which divides it from the left aspect of the esophagus. The greater curvature gives connection to the greater omentum, gastrosplenic, and gastrophrenic ligaments.

Surfaces

- Anterosuperior (Anterior) Surface: It faces forward and upward.

- Posteroinferior (Posterior) Surface: It faces backward and downward.

Parts

The stomach has 4 parts:

- Cardiac part (or cardia).

- Fundus.

- Body.

- Pyloric part.

Cardiac Part

It’s the part around the cardiac orifice.

Fundus

The fundus is the upper dome-shaped part of the stomach situated above the horizontal plane drawn in the level of cardiac notch. Superiorly, the fundus typically reaches the level of the left 5th intercostal space just below the nipple, thus gastric pain occasionally copies the pain of angina pectoris. The cardiac notch is located between the fundus and the esophagus.

- The fundus is usually distended with gas/air, that is plainly viewed as a radiolucent shadow under the left dome of the diaphragm in a skiagram.

- Traube space: It’s a topographic area overlying the fundus of the stomach that’s tympanic on percussion. It’s bounded superiorly by the lower border of the left lung, inferiorly by the left costal margin, on the left side by the lateral end of the spleen, and on the right side by the lower border of the left lobe of the liver.

Body

The body is the major part of the stomach between the fundus and the pyloric antrum. It can be distended tremendously along the greater curvature.

Pyloric Part

The pyloric part is the funnel-shaped outflow region of the stomach. A line drawn downward and to the left from an angular notch to the greater curvature divides it from the body. It stretches from the angular notch to the gastroduodenal junction. It’s split into 3 parts: pyloric antrum, pyloric canal, and pylorus.

- Pyloric antrum is the proximal wide part that is divided from the pyloric canal by an inconstant sulcus, sulcus intermedius present on the greater curvature. It’s about 3 inches (7.5 cm) long and leads into the pyloric canal.

- Pyloric canal is a distal narrow and tubular part measuring 1 inch (2.5 cm) in length. It is located on the head and neck of the pancreas.

- Pylorus (Greek gatekeeper) is the distal most and sphincteric region of the pyloric canal. The circular muscle fibres are noticeably thickened in this region, which control the discharge of stomach contents via the pyloric orifice into the duodenum.

- The position of the pyloric orifice is suggested on the surface by (a) a circular sulcus- pyloric constriction generated by the underlying pyloric sphincter or pylorus; and (b) the prepyloric vein of Mayo on the anterior surface of the pylorus.

Relations

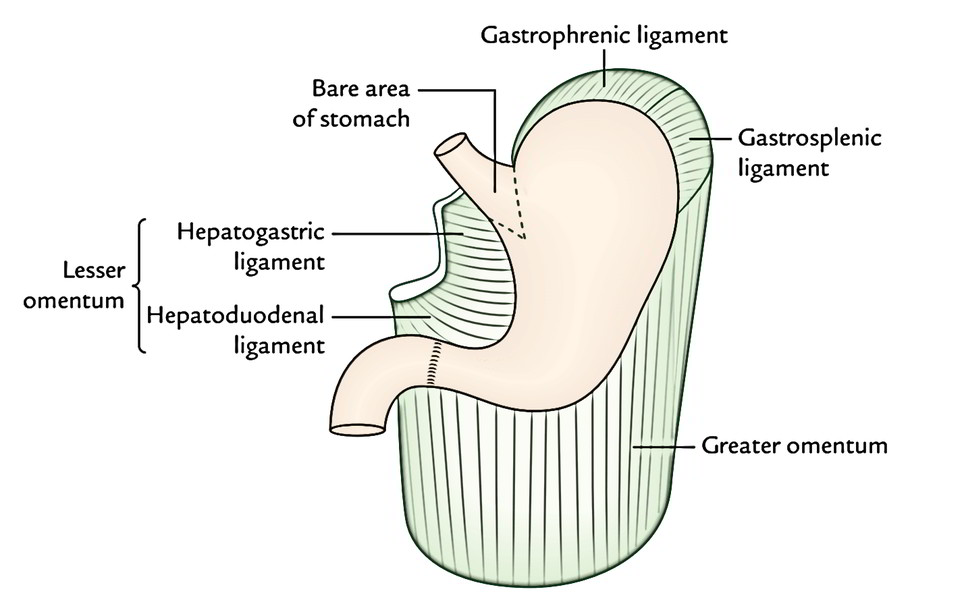

Peritoneal Relations

The stomach is covered by the peritoneum with the exception of where blood vessels run along its curvatures and a small area (termed naked area of the stomach) posteriorly near the cardiac orifice. The bare area of the stomach is directly related to the left crus of the diaphragm.

The peritoneal folds going from the lesser and greater curvatures of the stomach to other structures are as follows:

- Lesser omentum, stretches from the smaller curvature of the stomach to the liver.

- Greater omentum, stretches from the lower two-third of the higher curvature to the transverse colon.

- Gastrosplenic ligament, goes from the upper one-third of the higher curvature (i.e., fundus) to the spleen (near the hilum).

- Gastrophrenic ligament, stretches from the uppermost part of the fundus to the diaphragm.

Visceral Relations

Relations of the anterior (anterosuperior) surface:

- On the right side this surface is linked to the gastric feeling of the left lobe of the liver and near the pylorus to the quadrate lobe of the liver.

- The left half of the surface is related to the diaphragm and rib cage.

- The lower part of the surface is associated with the anterior abdominal wall.

Gastric triangle: It’s a triangular area of the stomach in contact together with the anterior abdominal wall. It’s boundedon the left side by the left costal margin, on the right side by the lower border of the liver, and inferiorly by the transverse colon. In entire esophageal obstruction, gastrostomy is done in this area to feed the patient.

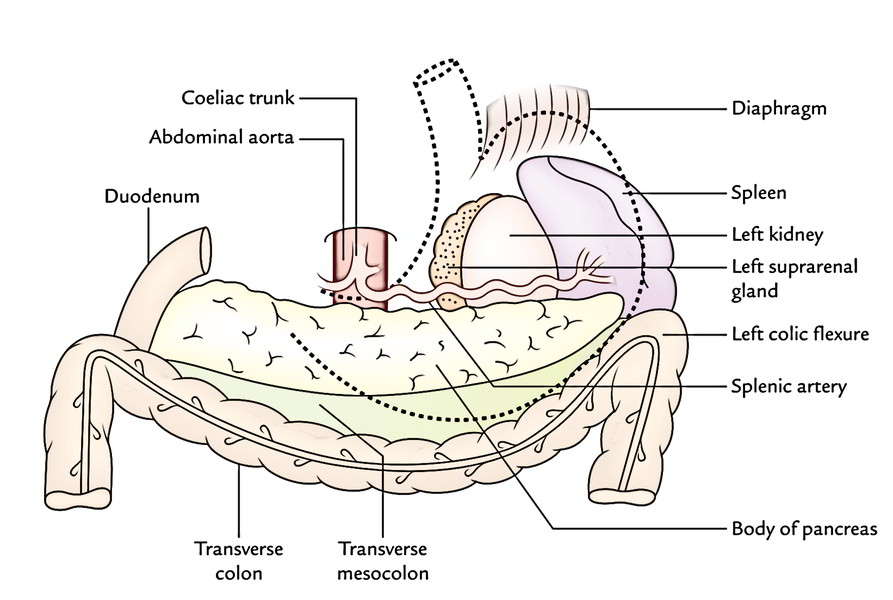

Relations of the posterior (posteroinferior) surface:

This surface is related to a number of structures on the posterior abdominal wall, which jointly create the stomach bed. These structures are:

- Diaphragm.

- Left kidney.

- Left suprarenal gland.

- Pancreas.

- Transverse mesocolon.

- Left colic flexure (splenic flexure of colon).

- Splenic artery.

- Spleen.

Mnemonic: “Dr S3 Kills Patients Mercilessly”.

D = diaphragm, S3 = splenic artery, suprarenal gland (left), and splenic flexure, K = kidney (left), P = pancreas, M = mesocolon (transverse).

All the structures creating the stomach bed are divided from the stomach by the lesser sac with the exception of spleen, that is divided from the stomach by the greater sac of peritoneum.

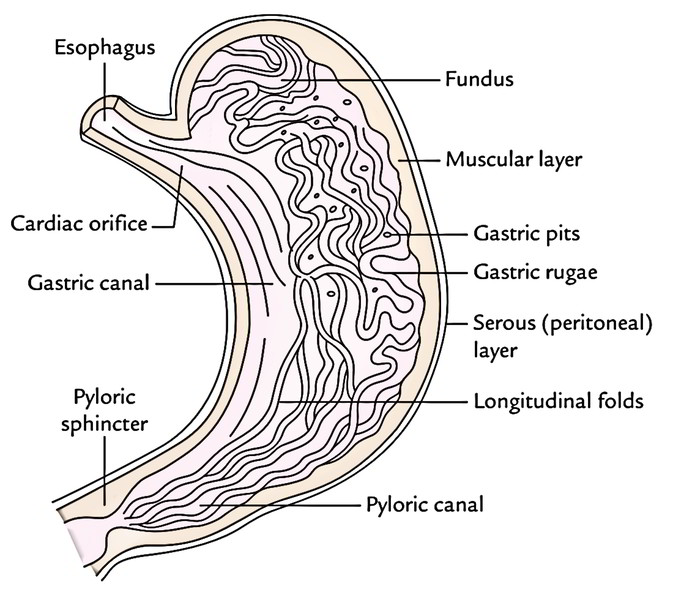

Microscopic Structure

The wall of the stomach is composed of 4 coats. From outside inward, all these are serous, muscular, submucous, and mucous coatings.

- The serous coating is composed by the peritoneum.

- The muscular coating contains 3 layers of unstriped muscles- outer longitudinal, middle circular, and inner oblique.

Close to the pyloric end the longitudinal muscle jacket divides into superficial and deep fibres. The deep fibres turn inward at the pylorus and join with circular muscle coating to help create the pyloric sphincter.

The circular muscle coat thickens at the pylorus to create a ring of muscle termed pyloric sphincter.

The major sphincteric component of the pyloric sphincter is originated from the circular muscle layer and its minor dilator component is originated from the longitudinal muscle coating.

- The submucous layer is made of loose areolar tissue.

- The mucous membrane is thick, soft, and velvety. It presents a number of temporary folds (rugae) which vanish when the stomach is distended.

- The mucous membrane of the stomach is lined by simple columnar epithelium which create simple tubular glands.

- Glands in the cardiac region secrete mucus.

- Glands in the fundus and body include mucus neck cells which secrete mucus, parietal/oxyntic cells which secrete hydrochloric acid and gastric intrinsic factor, and chief cells which secrete pepsinogen.

- Glands in the pyloric region secrete mucus.

Anatomically, the stomach is split into 4 parts, viz. cardia, fundus, body, and pylorus. Nevertheless, histologically the stomach is split into 3 parts, viz. cardia, body, and pylorus, because fundus and body share the common histological features.

Inside of The Stomach

When the stomach is cut open, the inner part of the stomach presents these features:

- Gastric folds/gastric rugae: The mucosa of an empty stomach is thrown into numerous folds termed gastric rugae. They can be longitudinal along the lesser curvature and irregular in the remaining part. The rugae are flattened when the stomach is distended.

- Gastric pits: All these are small depressions on the mucosal surface where open the gastric glands.

- Gastric canal (or Magenstrasse): A longitudinal furrow that creates briefly during consuming between the longitudinal folds of the mucosa along the lesser curvature. The gastric canal creates because of solid connection of the gastric mucosa to the underlying muscular layer, which doesn’t have an oblique layer at this site. This canal enables a fast passage of swallowed liquids along the lesser curvature to the lower part before it propagates to the different parts of the stomach.

Therefore, the lesser curvature is subject to maximum abuse of the swallowed hot food and irritable liquids (example, alcohol), which makes it susceptible to the gastric ulceration.

The inner part of the stomach can be directly analyzed in the living man by an endoscope. The gastric mucosa is reddish brown during life with the exception of in the pyloric part, where it’s pink.

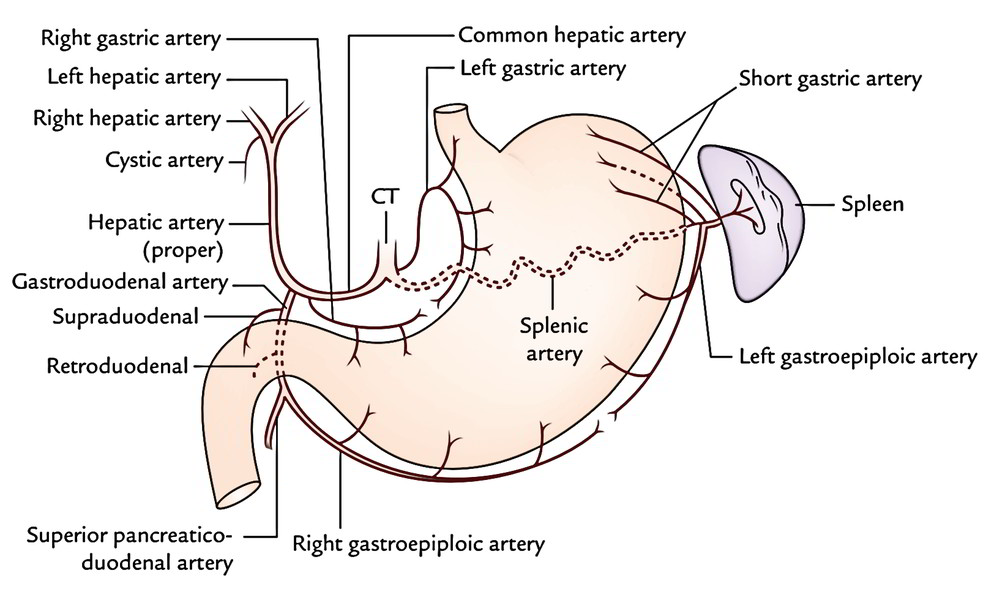

Arterial Supply

The stomach has abundant arterial supply originated from the coeliac trunk and its branches.

The arteries supplying the stomach are:

- Left gastric artery, a direct branch from the coeliac trunk.

- Right gastric artery, a branch of the common hepatic artery.

- Left gastroepiploic artery, a branch of the splenic artery.

- Right gastroepiploic artery, a branch of the gastroduodenal artery.

- Short gastric arteries (5 to 7 in number), branches of the splenic artery.

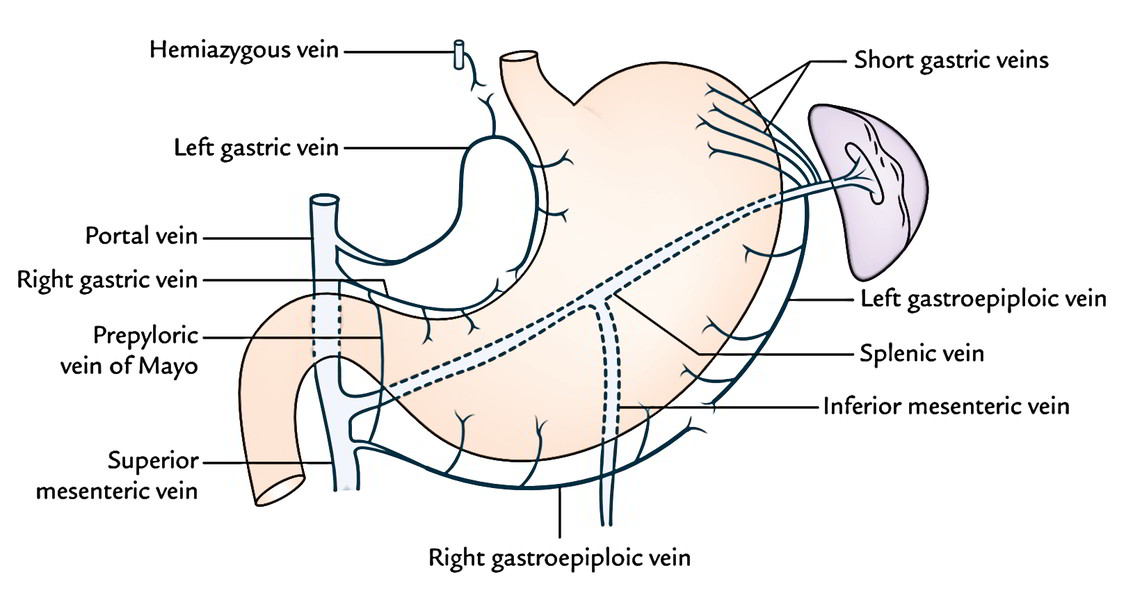

Venous Drainage

The veins of the stomach correspond to the arteries and drain directly or indirectly into the portal vein.

- Left gastric vein.

- Right gastric vein.

- Left gastroepiploic vein.

- Right gastroepiploic vein.

- Short gastric veins.

The right and left gastric veins drain directly into the portal vein. The left gastroepiploic and short gastric veins drain into the splenic vein. The right gastroepiploic vein empties into the superior mesenteric vein.

Lymphatic Drainage

The understanding of lymphatic drainage of the stomach is medically very significant because gastric cancer (carcinoma of stomach) propagates via the lymph vessels.

For illustrative purposes, the stomach is split into 4 lymphatic lands as follows:

First, divide the stomach into right two-third and left one-third by a line along its long axis. Now break up the right two-third into upper two-third (area 1) and lower one-third (area 4), and left one-third into upper one-third (area 3) and lower two-third (area 2). This way, 4 lymphatic lands are marked out and numbered 1 to 4.

Way of lymphatic drainage from 4 lymphatic territories into distinct groups of lymph nodes is as follows:

- Area 1 is the largest area along the lesser curvature. The lymph from this area is drained into left gastric lymph nodes along the left gastric artery. These lymph nodes also drain the abdominal part of the esophagus.

- Area 2 contains the pyloric antrum and pyloric canal along the greater curvature of the stomach. (The carcinoma of the stomach most often appears in this area.) The lymph from this area is drained into right gastroepiploic lymph nodes along the right gastroepiploic artery and pyloric nodes, which are located in the angle between the first and 2nd parts of the duodenum.

- Area 3 (also named pancreaticosplenic area) empties into pancreaticosplenic (pancreaticolienal) nodes along the splenic artery.

- Area 4 contains the pyloric antrum and pyloric canal along the lesser curvature of the stomach. The lymph from this area is drained into right gastric nodes along the right gastric artery and hepatic nodes along the hepatic artery.

The efferents from all these lymph node groups pass to the coeliac nodes. Efferents from coeliac nodes goes into the cysterna chylithrough intestinal lymph trunk.

Clinical Significance

Gastric Carcinoma (Gastric Cancer)

It typically appears in the region of pyloric antrum along the greater curvature of the stomach. The gastric cancer propagates by lymph vessels to the left supraclavicular lymph nodes. The enlarged and palpable left supraclavicular node (Virchow’s node) may be the first indication of gastric cancer (Troisier’s indication). The cancer cells get to the left supraclavicular lymph node via the thoracic duct.

Nerve Supply

The stomach has both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation.

Sympathetic Innervation

The sympathetic fibres are originated from T6 to T10 spinal sections via greater splanchnic nerves, and coeliac and hepatic plexuses. They get to the stomach by running along its arteries.

The sympathetic supply to the stomach is (a) vasomotor, (b) motor to pyloric sphincter, and inhibitory to the staying gastric musculature, and (c) acts as the main nerve pathway for pain sensations from the stomach.

Parasympathetic Innervation

The parasympathetic fibres are derived directly from the vagus nerves.

The anterior vagal trunk derived mostly from the left vagus nerve and partially from the right vagus nerve enters the abdomen on the anterior surface of the esophagus. Shortly after going into the abdomen it produces 3 branches in the neighborhood of the lesser curvature.

- Hepatic branch (or branches), which runs in the upper part of the lesser omentum to the porta hepatis to supply the liver and gallbladder. It also supplies a branch to the pyloric antrum.

- Coeliac branch, which follows the left gastric artery to the celiac plexus.

- Gastric branch/nerve of Latarjet (largest of the 3 branches), which follows the lesser curvature and disperses anterior gastric branches to the stomach as far as the pylorus.

The posterior vagal trunk derived mostly from the right vagus nerve and partially from the left vagus nerve enters the abdomen on the posterior surface of the esophagus; shortly after going into the abdomen it also supplies rise to 3 types of branches.

- Coeliac branchto the coeliac ganglion.

- Nerve of Grassiis the name given to one or more branches of the posterior vagal trunk which originates at the level of the gastroesophageal junction and supplies the gastric fundus.

- Gastric branch (nerve of Latarjet) which runs along the lesser curvature and supplies branches to the posterior outermost layer of the stomach.

The nerves of Latarjet supplies the acid and pepsin secreting regions of the stomach.

Clinical Significance

Vagotomy (A Surgical Procedure of Cutting The Vagus Nerves)

It’s done to heal the chronic duodenal ulcers. There are 3 distinct types of vagotomies:

- Truncal vagotomy: In this process the trunks of both gastric nerves are split at the lower end of esophagus.

- Selective vagotomy: In this process the hepatic and coeliac branches are maintained but the primary trunks of gastric nerves alongside nerve of Laterjet are cut.

The above 2 processes cause denervation ofpyloric antrum with following defect in gastric emptying.

Highly selective vagotomy: In this process only parietal cells of the stomach are denervated. The nerve of Laterjet is dissected out and cut. In this process gastric emptying isn’t changed, therefore it’s viewed by many as the process of choice in operative treatment of duodenal ulcer.

Gastric Pain

It’s generally referred to the epigastric region as the stomach is supplied by T6 T10 spinal sections.

Vagotomy

The vagus nerves mostly control the secretion of acid by the parietal cells of the stomach. Since excessive acid secretion is the chief cause of peptic ulcers, the section of vagal trunks (vagotomy) as they goes into the abdomen is performed to reduce the generation of acid. Vagotomy is of 3 types:

- Truncal vagotomy: In this both the vagal trunks (anterior and posterior) are sectioned at the lower end of the esophagus.

- Selective vagotomy: In this, the nerves of Latarjet are selectively cut to denervate the acid and pepsin secreting area of the stomach.

- The disadvantage of both truncal and selective vagotomy is that pyloric antrum is denervated. Hence the gastric emptying is changed.

- Highly selective vagotomy: In this only parietal cells of the stomach are denervated by cutting the anterior and posterior gastric branches, especially the nerve of Grassi. The edge of high selective vagotomy is that nerves of Latarjet and their antral branches are maintained. As a consequence, the gastric emptying stays normal.

(67 votes, average: 4.70 out of 5)

(67 votes, average: 4.70 out of 5)